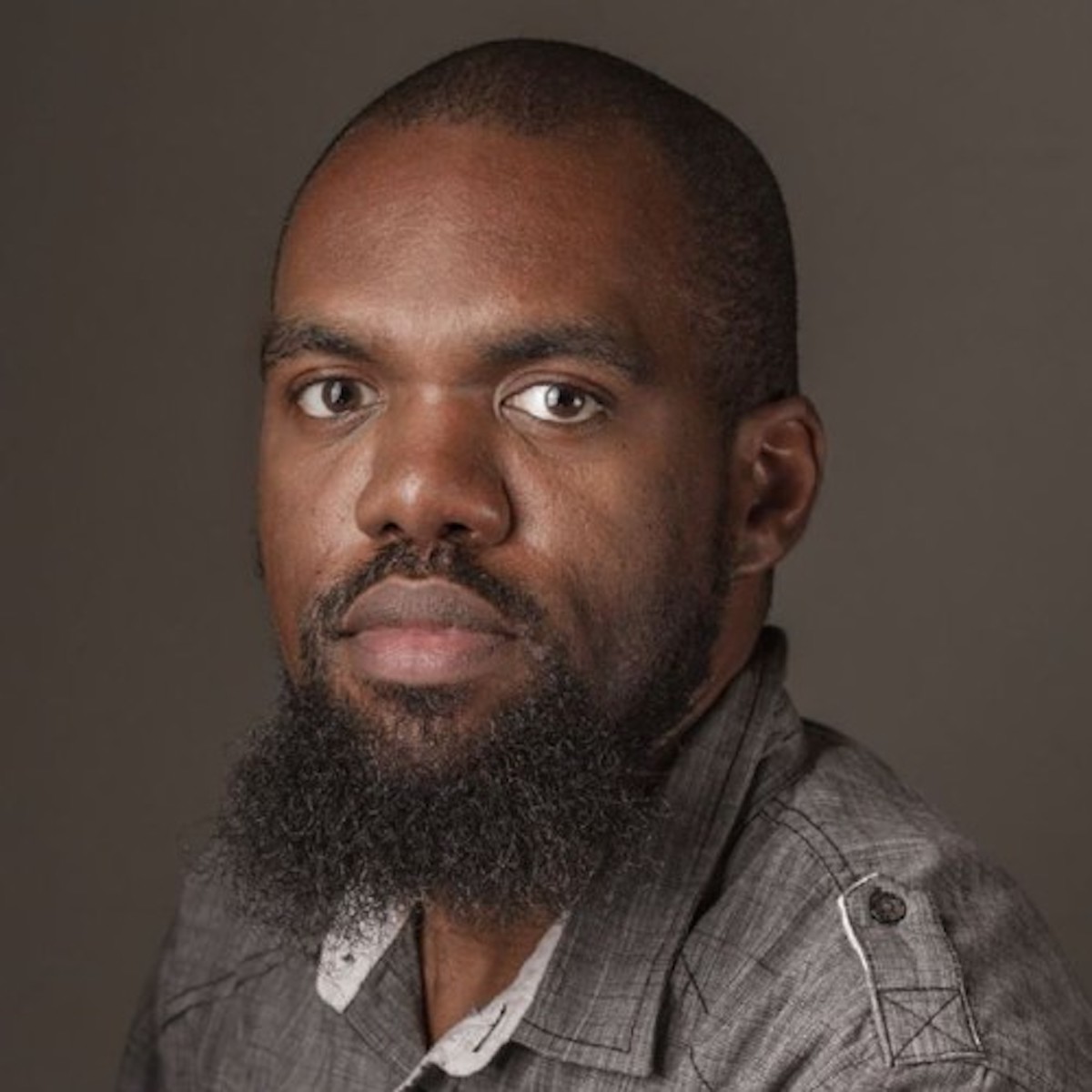

Guest blog by Christopher “Soul” Eubanks

I grew up infatuated with 90s hip hop music. Many of my favorite artists at the time, such as Nas, 2Pac, Outkast, and Ice Cube, often used their music to address issues of racial and social injustice. Much like these artists, I felt disconnected from the America that praised figures like Ronald Reagan and Christopher Columbus. Meanwhile, I related more to figures like James Baldwin and Malcolm X, who staunchly critiqued America for its shortcomings and hypocrisy.

In reading about the eating habits of Malcolm X, who ate a mainly vegetarian diet, I was inspired to become vegetarian at 17. I wouldn’t connect with the ethical philosophy of veganism until over a decade and a half later, when I began watching documentaries like Cowspiracy, Dominion and Earthlings. But I believe through listening to the artists of my generation share their accounts of being systematically oppressed, their experiences planted necessary seeds of rebellion within me. Those seeds would later cultivate me into the activist I am today.

“The average Black male, live a third of his life in a jail cell/ cause the world is controlled by the white male/ and the people don’t never get justice/ and the women don’t never get respected/ and the problems don’t never get solved/ and the jobs don’t never pay enough/ so the rent always be late, can you relate, we living in a police state”

“Police State” by Dead Prez

While I began to grow more and more frustrated with the realities of white supremacy, I found it important to not let my anger prevent me from being the best version of myself. This perspective has influenced my advocacy, as I aim my anger at systems of discrimination while having compassion and understanding for those that participate in these systems, be they slaughterhouse workers or people who consume animals.

One of the greatest motivating factors that convinced me to advocate for animals was discovering how the systems that exploit animals also exploit humans. As a Black man who grew up opposing white supremacy and colonization, I began to understand how my consumption of animals was playing a role in fueling the same systems of oppression that I so vehemently opposed. Year after year, decade after decade, I have seen endless footage of unarmed Black men and women killed at the hands of police. These acts of cruelty have made me question how so many people can see these same videos and not see systemic oppression. In the same way, it was through watching slaughterhouse footage to learn more about animal agriculture where I saw footage of normalized cruelty. Once again, I questioned how others could watch and make justifications for these systems of abuse.

Dick Gregory, a civil rights leader who marched with Dr. King, once said, “Because I’m a civil rights activist, I am also an animal rights activist. Animals and humans suffer and die alike.”

Factory farming poisons predominately Black and Latinx communities, diluting their air, water, and land with cancer-causing chemicals. Migrant and immigrant workers are predominately hired in slaughterhouses, burdened with exorbitantly high rates of physical and psychological harm from the job. Millions of acres of forest is destroyed to grow livestock feed, which permanently displaces Indigenous people from their ancestral land. These are only a few examples of the intersectionality between animal and human oppression. Eventually, I realized I could not oppose one without opposing the other.

The tools of oppression are interconnected for humans and nonhuman animals alike, but the corrupt systems in place work to obscure these lines. They want us to believe that veganism is a “fad diet”, reserved for the white and wealthy. When instead, it has become a powerful movement to mitigate unnecessary harm in our world for animals, and is fundamentally connected to the fight for human rights.

Even amongst humans, marginalized groups are often pitted against one another, made to believe their struggles are separate rather than deeply connected. This division creates a hyper-focus on groups fighting for their own rights and prevents collective organizing from taking place. Unfortunately, we live in a world where oppressed groups are competing against each other for the resources needed to achieve liberation.

This is colonized behavior, which promotes traditional capitalist notions of hyper-independence and self-reliance. Oppressed groups are rewarded when they focus solely on their own struggles, while unintentionally turning a blind eye to the oppression of those outside of their immediate group. Division is the insidious tool of colonization, which has been utilized by colonizing nations for centuries. It programs oppressed groups to view other oppressed groups as competition to their own liberation. This creates resentment and, ultimately, reinforces the thinking of the colonizer. It is crucial for anyone doing social justice work to have an intersectional framework—because no group can achieve true liberation in isolation.

I believe our most powerful resource in fighting oppression, and achieving collective liberation, is through understanding this: our oppression is interconnected.

As a person who is opposed to all forms of oppression and exploitation, I include nonhuman animals in my activism. Like humans, nonhuman animals deserve the moral birthright to not be born into systems that exploit them. Most of our society consumes animals and their by-products. This contributes to speciesism, the belief that humans are superior to animals, which is one of the most normalized forms of exploitation in our society. By separating the suffering of animals and humans, and creating a moral barrier between the two, it only fuels the cycle of oppression.

But violence begets violence. If we are willing to accept mass violence towards animals and the earth for our consumer needs for food, clothing, lab testing, and so on, then our society will continue to operate with violence and oppression as its fundamental framework. Immorality is unacceptable grounds to forge a better world upon. Collective liberation is impossible in such an unjust world, as cruelty and suffering is the opposite of peace.

It’s crucial for the betterment of our society to understand why we must adopt an anti-speciesist stance in our fight against oppression. Collective grassroots efforts must include nonhuman animals in their fight for liberation, as our oppression is inherently interconnected. As the famed civil rights activist, Fannie Lou Hamer once said, “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.”

Christopher “Soul” Eubanks is a social justice advocate, creative and public speaker raised in Atlanta, Ga that has dedicated himself to doing advocacy work that advocates for collective liberation. Christopher is the founder of APEX Advocacy, a non profit animal rights organization that develops grassroots activism and various campaigns to empower Black, Indigenous People of color to advocate for animal rights by defending their community against animal agriculture.